The Small and Large Intestines: Critical in Digestion

- anoushkapandit

- Oct 4, 2025

- 5 min read

Digestion is an essential process as it allows the body to extract nutrients from food and beverages as they are broken down into smaller compounds that are absorbed and used for energy, growth, and other cellular processes. For instance, proteins break down into amino acids, lipids break down into fatty acids and glycerol, and carbohydrates break down into simple monosaccharides like glucose and fructose. Each organ of the digestive system assists in moving the food through the gastrointestinal tract, breaking it down into smaller pieces, or performing both processes. The whole digestive process is controlled by a complex network of nerves and hormones. The organs consist of the mouth, esophagus, stomach, pancreas, liver, gallbladder, and intestines. In this article, the small and the large intestines will be discussed in detail.

Introduction to the Intestines

The term intestine is derived from a Latin root meaning “internal,” with the small and large parts making up the interior of the abdominal cavity. The small and the large intestines constitute the greatest mass and length of the alimentary canal, performing all digestive functions except ingestion.

The intestine extends from the stomach to the anus as a winding muscular tube, digesting food while also producing hormones that transmit chemical messages, regulating water levels, and preventing the invasion of germs. A complex system of nerves is also organized within the wall of the intestine, playing a significant role in sensing stimuli like mechanical changes or irritation that may trigger responses like diarrhea.

The Small Intestine

The small intestine is an organ that is three to five meters long in the gastrointestinal tract and is connected to the stomach. The small intestine breaks down food and fluids, absorbing over 90 percent of the nutrients and water that the body receives. The coiled tube of the small intestine is subdivided into three sections: the duodenum, the jejunum, and the ileum, as shown in the image below.

The duodenum is the shortest region, extending to 10 inches. It starts just below the stomach before curving to the right, back, down, and then to the left to form a C-shaped curve. It directs upward before joining the second region of the small intestine called the jejunum. The duodenum continues the breakdown of food and fluids into nutrients and water while also beginning the absorption process (transporting nutrients and water into the bloodstream).

Before reaching the duodenum, the partially digested food or fluid from the stomach transforms into chyme, which is a semiliquid, highly acidic mixture with various enzymes and digestive secretions, including hydrochloric acid. The duodenum releases a hormone called secretin that triggers the release of the bicarbonate enzyme that decreases the acidity of the chyme mixture, preventing the acid from damaging the small intestine.

The duodenum also releases a hormone called cholecystokinin that triggers other organs like the liver, pancreas, and gallbladder to release chemicals that transform the chyme into nutrients. Bile is released from the liver and the gallbladder, breaking down fats. Lipase, amylase, and protease are enzymes that are released from the pancreas to break down fats, carbohydrates, and proteins, respectively. The nutrients are then absorbed by the bloodstream.

The duodenum transports food molecules that don’t get absorbed in a peristaltic way into the jejunum, the second section of the small intestine. The jejunum extends to about 8 feet long, organized in multiple coils in the lower abdominal cavity. It consists of many blood vessels (giving this region a darker red color) and thick muscles that churn food continuously, creating a mixture with digestive juices. Peristalsis involuntarily occurs to keep food moving toward the last section of the small intestine.

The last section is the ileum, which extends to about 3.5 meters long. The ileum is responsible for absorbing nutrients from the digested food, including vitamins (primarily vitamin B12), minerals, carbohydrates, fats, and protein. It also functions in the reabsorption of conjugated bile salts. Compared to the jejunum, the ileum is thicker and more vascular with numerous developed mucosal folds. The jejunum and ileum are anchored to the posterior abdominal wall via the mesentery, a double fold of the peritoneum (a serous membrane). The ileum then transfers waste products toward the large intestine, joining the cecum at the ileocecal sphincter (a circular muscular valve).

The Large Intestine

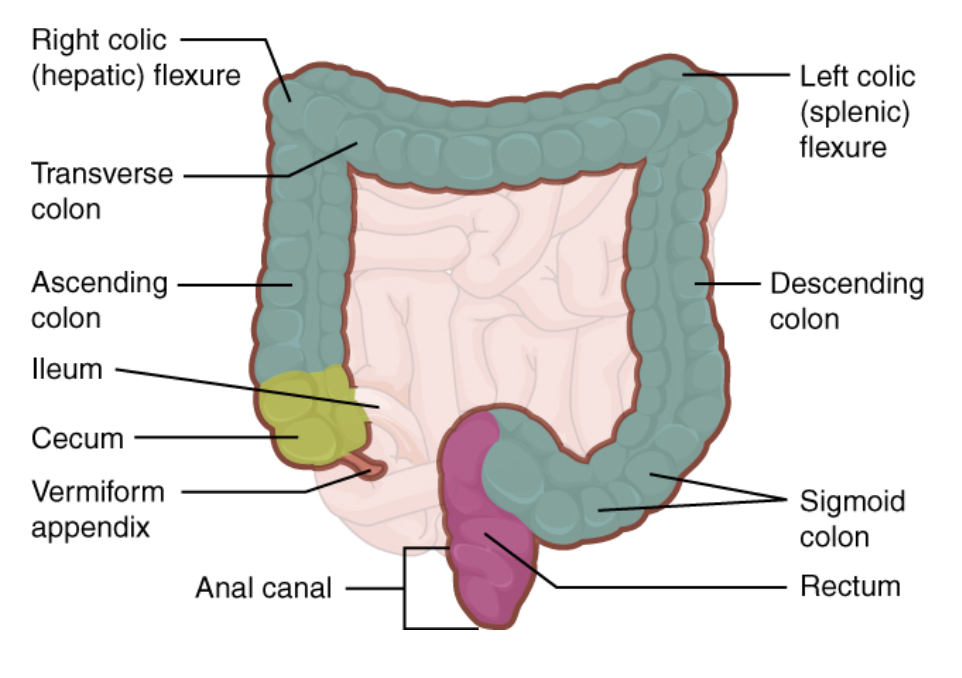

The large intestine is an organ that includes the colon, rectum, and anus in one long tube. It converts food waste into stool and eventually expels it from the body by peristalsis. The large intestine is primarily responsible for effective water and nutrient absorption as undigested fluids from the small intestine are received.

The colon is the first section of the large intestine that functions in processing food waste and eventually transferring it down to the rectum. The first subsection of the colon is called the cecum, which is about 3 inches long. It receives digested food waste from the small intestine, transferring it to the ascending colon (the second subsection). The ascending colon is 8 inches long, absorbing fluids and electrolytes from the waste products. The food waste is then moved to the next two subsections: the transcending colon (over 18 inches long) and eventually to the descending colon (6 inches long). During this movement, the food waste is gradually turned into a solid mass that resembles feces. The final step of this process occurs in the sigmoid colon (about 14 to 16 inches long), the last subsection of the colon.

The rectum is the second section of the large intestine that controls bowel movement and stores the feces until nerve signals trigger defecation. The rectum is about 5 to 6 inches long, and it gradually accommodates the waste from the colon. As it stores the feces, the rectum also functions in water and electrolyte absorption, solidifying the waste. It also involves mucus secretion for smooth passage.

The anus is the last section of the large intestine that contains muscle sphincters to manage how the waste leaves the body. The length of the anus is about 2 inches. The anus regulates bowel movement through the sphincters, functioning in releasing the feces when the rectum is filled with waste.

Works Cited:

Biga, Lindsay M., et al. 23.6 The Small and Large Intestines. Oregon State University

OpenStax, 2019.

Collins, Jason T., et al. “Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Small Intestine,” National Institutes of

Health. 18 February 2025.

“Duodenum,” Cleveland Clinic. 24 May 2024.

“In brief: How does the intestine work?” National Institutes of Health. 25 November 2021.

“Large Intestine & Colon,” Cleveland Clinic. 19 September 2024.

“Rectum,” Cleveland Clinic. 3 March 2023.

“Small Intestine,” Cleveland Clinic. 14 October 2024.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Ileum,” Britannica. 1 April 2015.

“Your Digestive System & How it Works,” National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and

Kidney Diseases. December 2017.

Assessed and Endorsed by the MedReport Medical Review Board