"I'll start studying in 20 minutes, I still have time": The Psychology behind Procrastination

- Samantha Sutherland

- Jan 9

- 3 min read

Procrastination - defined as the voluntary delay of an intended action despite anticipating the negative consequences - is a common self-regulatory failure which affects ones

academic, occupational, and personal functioning. Although often dismissed as laziness, psychological research reveals that procrastination is driven by emotional avoidance, cognitive biases, and neural mechanisms that prioritize instant mood repair. Understanding the psychology behind procrastination not only clarifies why it occurs, but also proposes the behavioural and clinical interventions that can help individuals break the cycle.

Procrastination as an Emotional Regulation Problem

Modern research emphasizes that procrastination is primarily an emotion-focused coping strategy. People delay tasks not because they are disorganized, but because the tasks evoke unpleasant emotions—anxiety, boredom, frustration, or fear of failure (Santos, 2023). Procrastination offers short-term emotional relief by removing the immediate source of discomfort, even though the long-term consequences are harmful. This “short-term mood repair” mechanism creates a reinforcing feedback loop: where avoidance temporarily reduces distress, but leads to guilt and reduced self-efficacy and stress, which in turn make a pattern of procrastination more likely. Methods that target emotional regulation are particularly effective. Mindfulness-based strategies, for example, help individuals tolerate uncomfortable emotions without resorting to avoidance. Cognitive reappraisal, reframing a task as meaningful rather than threatening, can also reduce the emotional intensity that drives procrastination.

Self-Regulation, Present Bias, and Motivational Failures

Procrastination is also linked to deficits in self-regulation. According to APS, procrastinators struggle to reconcile long-term goals with the desire for immediate emotional comfort. Cognitive biases, particularly present bias, lead individuals to overvalue immediate relief over future benefits. Motivation further influences procrastination where tasks perceived as tedious, overly complex, or likely to produce failure are more likely to be avoided. Behaviourally, interventions targeting self-regulation work because they reduce the emotional and cognitive barriers that trigger avoidance. Some of these methods include:

Implementation intentions (“if-then” plans): These help automate goal-related behaviours by creating concrete cues for action (“If it is 4 p.m., then I will begin my reading”).

Task chunking: Breaking large tasks into smaller, more manageable steps reduces cognitive load and reduces avoidance.

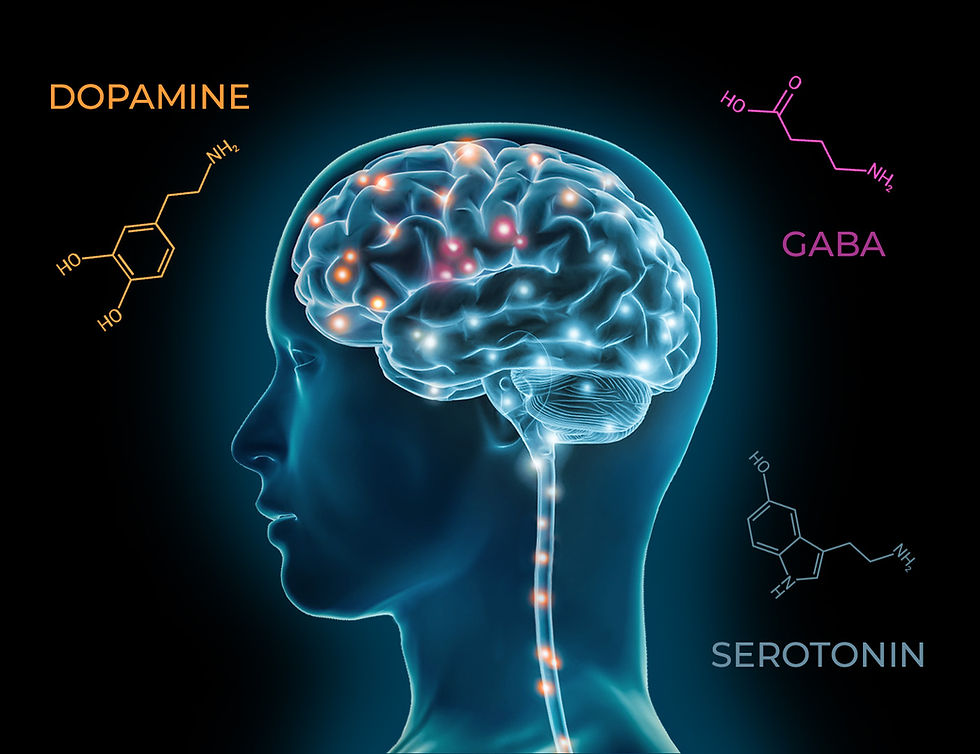

Reward substitution: Pairing an unappealing task with a small immediate reward increases dopamine-driven motivation and counters present bias.

The “10-minute rule”: Committing to work for only ten minutes often helps overcome initial resistance and improves task initiation.

Neuroscientific Foundations of Procrastination

Neuroscience research highlights an internal struggle between the prefrontal cortex (PFC), responsible for planning and long-term decision-making, and the limbic system, which seeks immediate gratification. Under stress or emotional strain, the limbic system can overpower the PFC, shifting priorities toward short-term comfort. Dopamine release patterns also shape procrastination, so low dopamine tasks feel less rewarding which encourages individuals to seek out more stimulating distractions.

This neurological perspective supports both behavioural and clinical interventions:

Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT): Helps regulate the emotional triggers that activate the limbic reward system and undermine executive control.

Environmental restructuring: Minimizing digital distractions limits external triggers that exploit the brain’s reward circuitry.

Exercise and sleep regulation: These enhance PFC functioning, making long-term planning easier and reducing reliance on emotion-driven impulses.

Mental Health, Perfectionism, and Clinical Considerations

Procrastination frequently coexists with mental health challenges such as anxiety, ADHD, and depression. Perfectionism is especially relevant, individuals who fear making mistakes may delay tasks to avoid confronting potential failure. Chronic procrastination can also damage self-esteem, intensify stress, and contribute to a cycle of shame and avoidance. These clinical interventions demonstrate that procrastination is not a moral failing but a modifiable psychological pattern, therefore play an important role:

CBT for anxiety and perfectionism: Targets irrational beliefs (“If I can’t do it perfectly, it’s not worth doing”), improving task initiation.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT): Encourages individuals to act according to values even in the presence of discomfort, reducing experiential avoidance.

Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT) skills: Emotion regulation and distress tolerance strategies help individuals remain engaged with challenging tasks.

ADHD-specific interventions: Behavioural activation, medication, and structured routines can significantly reduce procrastination rooted in executive dysfunction.

Conclusion

Procrastination is a multifaceted behaviour rooted in emotional avoidance, cognitive distortions, and neurobiological dynamics between the limbic system and executive control networks. While procrastination provides temporary mood relief, it ultimately undermines goals and well-being. Fortunately, a wide range of evidence-based behavioural strategies—such as implementation intentions, task chunking, and reward substitution—as well as clinical interventions, including CBT, ACT, and mindfulness-based therapies, can help individuals address the emotional and neurological drivers of procrastination. Recognizing procrastination as a psychological phenomenon rather than a character flaw is essential for reducing stigma and supporting meaningful behavioural change.

References

Deconstructing Stigma. (n.d.). Procrastination. https://deconstructingstigma.org/guides/procrastination

Insights Psychology. (n.d.). The neuroscience of procrastination. https://insightspsychology.org/the-neuroscience-of-procrastination/

Psychology Today. (n.d.). Procrastination. https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/basics/procrastination

Santos, M. (2023). Why wait? The science behind procrastination. Association for Psychological Science Observer.

Assessed and Endorsed by the MedReport Medical Review Board