Healing from the Inside Out: The Microbiome Gut-Brain-Axis and Minority Mental Health

- Rachelle DiMedia

- Jul 28, 2025

- 40 min read

Introduction:

Most people are unaware of the intricate connection between the gut and brain, known as the gut-brain axis (also referred to as the microbiome-gut-brain axis or GBA). Gut bacteria play a crucial role in mood, stress levels, and mental disorders like depression and anxiety, via the GBA. Disturbances in the balance between gut bacteria, known as dysbiosis, cause dysregulation of the bidirectional pathways between the gut and brain, leading to a wide array of neurological and gastrointestinal (GI) disorders. The GBA is a sophisticated system of communication that scientists are only now beginning to comprehend. It is essential to understand how this affects your body and mind to achieve optimal health. However, as new science emerges and breakthroughs occur, is this information and care available to everyone? Even now, despite advances in medicine, technology, and transportation, access to proper education, food, and medical care is limited for many minority populations. What can be done to address this and ensure access for all?

Research is being conducted to enhance dietary recommendations and provide treatment for the nutritional deficiencies affecting a significant number of people worldwide. There is an ever-growing number of supplements, therapies, and nutritional approaches being offered, but not all of them have adequate scientific evidence to support their claims. The more you know, the better you can take control of your overall health.

Mental health is deeply intertwined with physiological processes that extend beyond the brain itself. Research shows that gut bacteria can influence mood, stress response, and even mental disorders like anxiety and depression. However, minority communities often face higher levels of chronic stress due to systemic inequities, racial trauma, and healthcare disparities—factors that can harm gut health.

For many marginalized groups, cultural traditions, dietary habits, and access to mental health care play a crucial role in being able to maintain well-being. Although there has been progress in awareness and treatment options, minorities still encounter barriers to optimizing their mental health. These communities often face obstacles to treatment, stigma surrounding mental illness, and limited access to nutritious foods that support gut microbiome balance. Due to endemic inequality, minority populations also face higher levels of stress from racial trauma, pollution, and disparities in healthcare and housing—a combination of factors that affect the GBA and, in turn, mental health. A universal understanding of the gut and overall health can not only open new doors for comprehensive healing approaches in the medical community, but it can also enable all of us to be more proactive in our care.

In recognition of Minority Mental Health Month in July, this paper will examine the role of the GBA axis and overall health, including its impact on mental well-being, and examine barriers to proper nutrition in marginalized populations. It will propose holistic options that society could use to improve mental well-being for everyone.

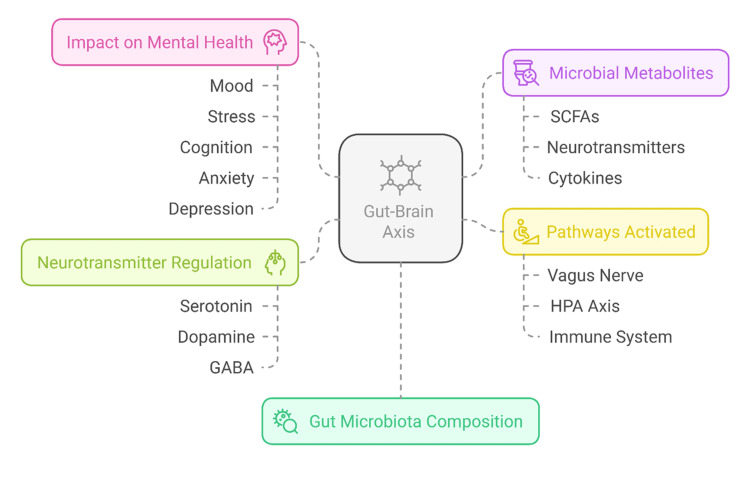

The Gut Microbiome-Brain Axis (GBA): How Microbes Influence Mental Health(1-4,5,12,13)

You are not one single organism, but rather a superorganism comprised of many parts. It is not widely known, but human cells make up less than half of your body, and the rest is comprised of trillions of microorganisms, predominantly bacteria, that colonize and live in your body. It is collectively known as your microbiome. You need the bacteria because they play key roles in regulating various physiological functions, including digestion and mental health. They need you because they need a home, and the human body is the ideal habitat, especially when it's healthy. The microbiome is unique to each individual and is influenced by various factors.(1,2)

The GBA is a complex communication system involving continuous crosstalk between the gut and the brain. This bidirectional communication involves neuronal, endocrine, and immune mechanisms.

The gut is home to the enteric nervous system (ENS), which maintains the digestive system. It is a network of independent nerves, allowing it to function independently of the central nervous system (CNS), which includes the brain and spinal cord. Within the ENS are your gut microbiota (a group of microorganisms), which produce substances active in the brain and immune system. These substances support the structure and function of brain regions responsible for emotion, cognition, physical activity, and gastrointestinal (GI) homeostasis. The fact that GI disorders often overlap with CNS disorders is well-known. For example, as many as ⅓ of IBS patients also suffer from depression, and many people afflicted with mental health disorders display a wide range of GI disorders. How does this connection operate?

The microbiome, a collection of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microbes residing in the digestive tract, metabolizes the food and drink you ingest, extracting nutrients for your body as they do. The gut microbiota works with the digestive tract in several ways: (1,2)

Promoting digestion by assisting the absorption of nutrients or by the fermentation of some foods to generate important metabolites used in the body.

Supporting gut mucosa (the lining of the stomach) by assisting in the make-up of the GI mucus and the enzymatic activity of the mucosa.

Acting as a barrier to pathogens and toxins, with some bacteria even releasing antimicrobial agents for protection.

Metabolic energy utilization

Immunomodulation (modifying the immune response to a desired level)

Each part of the GI tract hosts distinct colonies of bacteria that exert various effects on the microbiome. Nutrients flow in and out at multiple locations, all of which are influenced by numerous factors, including age, medications, ethnicity, and overall health.

How is information transmitted to the brain? There are multiple neural connections between the gut and brain, with the Vagus nerve serving as the primary pathway. This information superhighway is surprisingly mainly one-directional. Approximately 80-90% of vagal nerve fibers are afferent, meaning they carry information from the gut to the brain, rather than vice versa. Additionally, your gut communicates with your brain through hormones, immune system molecules, and microbial metabolites, forming a complex, dynamic feedback loop between the two. Your microbiota constantly informs the brain about everything from nutrient levels and pathogens to cognition and emotional states.

The microbiome also plays a crucial role in regulating neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid), and acetylcholine, all of which are essential for brain function. In fact, 90% of serotonin is produced in the gut, not the brain5. This collection of microorganisms influences the way you think, behave, perceive, and feel. The connection is so profound that some scientists have begun referring to it as the “second brain.” You’ve experienced the effects of stress in your gut when you have felt butterflies or been sick with worry. However, science is just beginning to realize that your gut isn’t just reacting to your brain; it is actually generating some of the emotions themselves. Several recent neuroimaging studies have strengthened the evidence that microbiome alterations are correlated with brain function.

Mental Health:

Anxiety and depression are ubiquitous in our society today. It is projected that depression will be one of the top health concerns by 2030, significantly contributing to a society-wide decreased quality of life and reduction of workforce due to disability claims. Recent studies suggest that maintaining a healthy gut microbiome through a balanced diet and lifestyle can improve mood regulation, reduce inflammation, and even alleviate symptoms of existing and tough-to-treat mental illnesses. Researchers have found that people with mental health disorders have altered gut microbiomes, showing a lack of beneficial bacteria and increased levels of harmful bacteria. This can influence how they process emotions, decision-making, and everyday stressors, creating harmful levels of inflammation and contributing to additional physical and emotional issues.

We are still learning how the gut and brain modulate each other's functions, but there is no doubt that this highway of information is essential to our overall well-being. The GBA plays a significant role in maintaining your mental health. Dysbiosis leads to inflammation, which has been linked to poor overall health.

Cognition (Memory, Focus, Learning): The microbiome influences the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which supports the growth of new neurons (brain cells). BDNF is crucial for learning and long-term memory. Low levels have been associated with:

Cognitive decline

Depression

Alzheimer’s disease

Children: Gut health plays a crucial role in early brain development. When children experience poor gut health—often due to inadequate nutrition or limited dietary choices—it can lead to difficulties in learning, information retention, behavioral issues, and impaired impulse control. Additionally, this poor gut health may contribute to the development of neurodegenerative and mental disorders.

The gut-brain axis (GBA) is also associated with neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Research has revealed alterations in the gut microbiome of children with these conditions, who frequently exhibit gastrointestinal (GI) issues. For instance, children with ASD often have higher levels of harmful bacteria that produce inflammatory compounds. Encouragingly, several small studies suggest that improving gut health can lead to better behavior, communication skills, and GI symptoms in children with ASD.

Aging: As we age, our microbiome changes, and microbial diversity declines. The Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) becomes more permeable, and inflammation levels rise. Good species of bacteria are replaced with inflammatory bacteria that may contribute to the development of age-related diseases, cognitive decline, and dementia. This has been referred to as “inflammaging.”5

However, a study published on June 30, 2025 (15) challenges the common belief that inflammation is a normal part of aging. The findings indicate that it may actually be the effects of our environment—people in nonindustrialized regions age differently from those in industrialized areas. The study found that inflammation increased with age in more industrialized nations, while this was not observed in non-industrialized countries. These results suggest that aging may be more influenced by lifestyle and environmental factors, such as pollution, diet, and physical activity, than by the aging process itself. The inflammation seen in indigenous populations was caused by bacteria, viruses, and parasites, which could be considered beneficial responses. Also, their inflammation levels did not rise over time. In contrast, urban populations showed inflammation associated with early stages of chronic diseases, with levels increasing as they aged. The study also indicates that people in urban communities or those exposed to higher levels of pollutants and toxins are at greater risk for inflammation-related diseases. The researchers concluded by recommending that individuals adopt a healthier diet and exercise more to better manage their immune response to their living conditions.

Leaky gut: The gut barrier becomes more permeable, allowing undigested food particles, toxins, and microbes to escape into the bloodstream, triggering an immune response and widespread inflammation throughout the body. This impacts the brain, leading to neuroinflammation, which has been linked to cognitive impairments and emotional dysfunction. The risk of leaky gut is higher in older individuals, but it can also occur in younger age groups, especially among those with unhealthy habits.

Evidence of the microbiome-brain link (1,2,4,5,12,13)

Significantly affecting mental health, the gut–brain–immune axis exhibits a complex interaction between the gastrointestinal tract, immune system, and central nervous system. Until recently, the only evidence showing that the microbiota in your gut influences your brain came from animal-based studies. Now, however, human studies are being done that indicate this connection is real and extremely important to your mental health.

There are multiple theories to explain the reasons for mood disorders, anxiety and depression, in particular. While it is believed that they are related to alterations in chemical pathways involving the brain and the HPA axis, as well as sleep patterns, thyroid levels, immune function, and the mental health disease state itself, it is likely a combination of all these factors. Researchers are beginning to recognize that bodywide connections and holistic treatment, although complex, may be the key to addressing a wide range of illnesses, both physical and emotional. The food we consume has a significant impact on our overall health. Evidence suggests that following a balanced diet, along with the appropriate supplements, may be essential for maintaining optimal health.

Although it is considered a relatively new field of study, the microbiome-brain connection has been extensively studied. The International Human Microbiome Consortium (IHMC) was established to investigate the role of the microbiome in human health and disease, and to prevent and treat disorders related to this link. Their research showed significant evidence for the relationship between the gut and metabolic, neurologic, and autoimmune disorders. Dysbiosis can affect almost all of our organs and systems, including the CNS, contributing to multiple disease states, both physical and emotional: (1,6)

Cancers

Infections

Allergies

Immune and autoimmune diseases

Crohn’s disease, Ulcerative Colitis, and Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Functional dyspepsia, constipation, and celiac disease

Neurodegenerative disease: Autism Spectrum, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s

Neurodevelopmental disorders

Anxiety, depression, anorexia, and mental health disorders

Cardiovascular diseases

Metabolic disorders: diabetes, obesity

Most bacteria in the GI tract are benign, while some are pathogenic, meaning they cause disease. When harmful bacteria are allowed to multiply uncontrollably, there are serious threats to the host, which is you. When the microbial balance is disrupted by diet, stress, or environmental factors, it can contribute to neurologic as well as mental health disorders. The diversity of bacteria and their interactions can affect signals transmitted to your brain via chemical and neural pathways from your digestive tract. When you don’t have a proper diet, it decreases microbiome diversity, which can negatively impact your mental health. For example, recent studies have found that people with altered sleep, people with schizophrenia, and people with ASD have unique gut microbial profiles, containing increased growth of harmful proinflammatory bacteria and lacking protective species.

Factors that influence gut microbiota and lead to dysbiosis:

Biological: Starting from before you were born, even the maternal environment and method of delivery influence your microbiome composition. As we age, alterations in the GBA can predispose us to disease

Lifestyle choices: Lack of physical exercise, smoking, alcohol consumption, stress, and sleep disruptions

Diet: Diets high in animal products and low in plant-based choices

Stress: Especially chronic stress, exerts a negative effect on the microbiome via catecholamine release and neuroendocrine hormones that alter gut permeability and signaling pathways with the brain

How exactly are the bacteria in your gut talking to your brain? Science has not yet discovered the exact mechanism that enables this, but several possible routes have been identified.

PATHWAYS OF INTERACTION BETWEEN THE GUT AND BRAIN (1,2,12,13)

The gut-brain theory proposed that the gut microbiota influences brain function through mechanisms like the vagus nerve, neurotransmitter production, and immune system regulation:

Neural Route: Bacteria in the gut produce chemicals that influence signals being sent back and forth between the millions of nerve endings in the digestive system and the brain via the vagus nerve, which runs from the colon to the brain stem.

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs): These metabolites, derived from dietary fiber and produced in the colon, play a vital role in modulating inflammation and directly influencing the production of CNS neurotransmitters (serotonin, dopamine). SCFAs also modulate the activity of the vagus nerve, which in turn impacts brain function in areas responsible for mood regulation, stress response, and cognitive function.

Microbiota play a crucial role in producing essential neurotransmitters, such as serotonin, dopamine, and GABA, which are vital for brain function. These neurotransmitters influence mood, sleep, pleasure, reward, motivation, emotional regulation, and gut sensation. Mentioned earlier, 90% of serotonin is produced in the gut, where it regulates motility, pain, nausea, and secretion. Furthermore, the gut affects serotonin levels in the bloodstream, which are then processed by the central nervous system (CNS).

Vagus nerve: This nerve facilitates bidirectional communication between the gut and brain. It transmits sensory information to the brain for processing and controls motor functions in the GI tract (motility, secretion, and absorption). The Vagus also regulates the ENS and the inflammatory-immune response.

Stress produces various beneficial substances generated in the gut, but chronic stress can inhibit their release, leading to altered emotional responses and has been linked to conditions such as depression.

Immune Route:

Cytokines: Receptors on intestinal walls activate cytokines, signaling proteins that facilitate communication between cells and play a key role in regulating inflammation and the immune response. They can cross the BBB and affect brain function by altering neurotransmitter levels essential for mood and cognitive function (GABA, serotonin, dopamine). Inflammation further exacerbates the immune-stress response and activates the HPA.

Microglia: Specialized immune cells in the CNS that protect against infection and remove damaged cells and other debris. Gut microbial metabolites influence their activation, regulating pathways responsible for learning, memory, behavior, and brain function.

Signals from the gut can increase BBB permeability, allowing the passage of inflammatory mediators into the brain, leading to neuroinflammation.

Endocrine/Hormonal Route: The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) and gut hormones create a feedback loop between the brain and endocrine system that controls the release of hormones (cortisol) in response to stress. Gut microbiota can modulate the HPA axis through microbial metabolites that influence cortisol levels. Dysbiosis can lead to an exaggerated stress response, resulting in increased cortisol levels, which in turn further exacerbate gut permeability and inflammation. Cortisol impacts mood, cognition, and inflammation.

Reference: 12 Microbiome alterations disrupt these routes and contribute to mental health and neurodegenerative disorders, as well as brain issues and neural alterations that contribute to and worsen dysbiosis. It remains unclear whether disruptions in gut microbiota or mental health are to blame, but an interconnected, cyclical pattern is likely at play.

Mood disorders alter the microbiome, leading to changes in eating habits, decreased physical activity, and impaired gut motility and function.

Diets high in fat and sugar have been linked to depression, further promoting dysbiosis, which will, in turn, worsen mood disorder symptoms.

Dysbiosis creates increased barrier permeability (leaky gut), allowing toxins to enter the bloodstream, creating systemic inflammation.

Chronic stress activates the HPA axis, which releases cortisol, altering gut permeability and reducing the growth of beneficial bacteria while promoting the growth of harmful bacteria.

Maintaining or restoring microbial balance to enhance mental health outcomes shows promise through therapeutic approaches, including dietary changes, along with pharmaceutical and non-pharmacological therapies, like biotics.

Potential Treatments and Prevention (11,12)

Your microbiome is highly variable and can change in response to multiple factors, including:

Dietary choices

Exposure to stress

Environmental conditions

Certain medications (especially antibiotics)

Life stage

Medical disorders

Some medical procedures.

Research has revealed significant connections between gut microbiome health and diversity, as well as its influence on brain function and emotional well-being. Modern habits like a poor diet, high in processed foods, lead to dysbiosis, leaky gut, and inflammation. Chronic stress, poor sleep habits, and a sedentary lifestyle exacerbate the damage. However, the GBA is markedly resilient, and it can be restored with the right lifestyle choices and treatments. Maintaining gut microbiota equilibrium and addressing dysbiosis may be a practical therapeutic approach to enhance patient outcomes, including better brain function and overall health. However, this isn’t easily attainable for everyone.

Psychiatric conditions are among the leading causes of worldwide disability, affecting nearly 1 in 4 people. Although traditional synthetic medicines have made monumental strides, and many have become more target-specific and effective, they have only managed to advance slightly in the last 30 years, with just 30-50% of all affected people slightly responsive or nonresponsive to current options. Also, they often come with adverse side effects and can be inconvenient for the patient. In addition, most medicines do not address dysbiosis. They, therefore, may not be treating the root cause, meaning they can alleviate some symptoms but do not address the origin of the disease. In addition, traditional psychotropic medications, used to treat mental disorders, can negatively alter the microbiota. For example, some have antibacterial properties that reduce microbial diversity. However, there are some promising new treatments and recommendations to help you achieve optimal health.

DIET AND LIFESTYLE RECOMMENDATIONS (2,4):

Our diet plays a crucial role in our mental health. Emerging evidence suggests that insufficient or inadequate nutrition is associated with an increased risk of poor psychological health and impaired brain function. Your GBA affects nutrient absorption and utilization, which, in turn, directly impact cognitive processes, mood regulation, neuroplasticity, and other factors related to mental health.

Luckily, your microbiome will respond to changes in dietary modifications. You can achieve good GBA health with proper nutrition, even if you haven’t always had the best habits. Previously, research was primarily driven by nutritional deficiencies, whereas emerging research has focused on daily dietary habits over time and their impact on overall well-being. The newer but growing fields of lifestyle psychiatry and nutritional neuroscience have shed light on the fact that diet not only provides physical sustenance, but it is also essential for cognition, emotional states, mental health, and brain functioning.

NOVA and UPFs:

There has been a worldwide increase in the consumption of UPFs (Ultra-Processed Foods). Studies have shown that consumption patterns are consistent across gender and race, with global consumption increasing post-COVID. UPF, known for containing excessively high amounts of refined sugars, saturated fat, trans-fat, caffeine, and sodium, as well as low levels of fiber, is a significant factor contributing to human illness.

The NOVA food classification system has been increasingly used to evaluate the relationship between the extent of food processing and health outcomes. It classified UPFs as category 4, “food substances of no or rare culinary use”. These food products are created to maximize profitability by using low-cost ingredients with a long shelf life and by emphasizing branding. They are engineered to cost less, be convenient, and to taste unusually good (hyperpalatable). Studies have shown an increased risk of multiple diseases, both physical and mental, with higher consumption of UPF. This may be due to an altered immune system, increased inflammation, and disruptions in the HPA axis. The NOVA classification has been utilized in multiple countries and by international organizations to inform food and nutrition policies, as well as to support public health campaigns and researchers in enhancing human health outcomes and promoting sustainable food practices.

Feeding the brain:

The brain takes up 20-25% of the body’s total energy needs and requires specific nutrients for optimal functioning. You must eat the right foods to ensure your brain is well-nourished, and maintaining a balance between the immune system and brain function depends on the health and diversity of your gut bacteria.

Carbohydrates: Provide glucose, the primary source of energy for the brain.

Essential fatty acids: (Omega-3, Omega-6) play a critical role in maintaining the integrity of brain structures and promoting the synthesis and functioning of neurotransmitters, as well as regulating immune system processes.

Amino acids: Derived from protein, including tryptophan, tyrosine, histidine, and arginine, are used to produce neurotransmitters and neuromodulatory compounds.

So, how can you create an optimal microbiome? Your choices are yours, and your microbiome is individual to you, so there is no particular algorithm that will work for everyone. However, some or all of these solutions will contribute to a healthier gut and, therefore, a healthier brain:

Eat a diet rich in plant-based foods, fermented products, and healthy fats will allow the good bacteria in your gut to grow and thrive.

Whole grains, legumes, and vegetables contain a good amount of dietary fiber. This promotes the growth of SCFAs in the colon, which reduces inflammation and neuroinflammation, thereby improving brain function

Fermented foods (yogurt, kefir, and kimchi) are rich in probiotic bacteria. Eating these will enhance microbial diversity and production of neurotransmitters to the brain (serotonin, dopamine)

Berries, tea, and dark chocolate contain polyphenols, which create anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects

Reduce UPFs, such as processed foods and refined sugars

Eat lean meats like chicken and turkey, and limit others

Drink plenty of water and engage in regular physical activity to promote optimal gut diversity and motility (movement).

Manage stress with meditation, deep breathing, and therapy.

Prioritize sleep

Limit unnecessary antibiotic use

Spend time in nature

Is there a diet available that you could base your choices on? The anti-inflammatory and Mediterranean diets are similar and are often recommended, as they are known to reduce inflammation.

The Mediterranean Diet: It Might Be Able to Keep You Healthier and Happier

(3, 5,13)

It is well known that the Mediterranean diet offers numerous heart-healthy benefits, but did you know it also benefits your mental health? Due to its diverse nutritional suggestions, it encourages a healthy gut microbiome. The diet consists mainly of eating fiber-rich fresh fruits, vegetables, beans, lentils, nuts, whole grains, and olive oil, with occasional servings of fish, chicken, eggs, and dairy products. Avoidance of red meat and sweets is suggested. A wide range of microbes in the gut can thrive due to the diverse array of plant products that support different bacterial health. The GBA benefits of the Mediterranean diet have been thoroughly studied and show that adhering to this diet decreases the chances of anxiety and depression.

When lifestyle modifications aren’t enough:

Recent advances have led to a better understanding of the GBA and its role in contributing to disease states when it is altered. There is ongoing research looking into how to prevent and treat diseases and mental health disorders linked to dysbiosis, using various methods when lifestyle modification isn’t enough. Let’s explore these.

“BIOTICS”:

(1,2,3,5,6)

Biotics (an informal term encompassing all of them): Substances that support the GBA and overall health, including prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics, psychobiotics, and postbiotics. Altering your gut with biotics may be beneficial for your overall physical and mental health. Numerous animal and human studies have demonstrated improvements in mood, learning, and memory with the use of biotics. There is extensive evidence demonstrating their effectiveness in restoring gut microbiota and in treating physical and mental disease. Microbiome modulation has become an attractive target for biotech companies in the development of novel pharmaceuticals and therapeutics. However, despite scientific advances showing their benefits, biotics are still classified as dietary supplements rather than medicines, which restricts their application.

Since the effect of most antidepressants is actually relatively small, evidence shows that probiotics and psychobiotics might offer the same amount of benefit as commonly prescribed psychoactive medications, but without the dangerous withdrawal and side effects. In addition, twin studies have indicated that adjusting the microbiome may be able to override genetic predisposition to common disorders like depression. Researchers are focused on the effects of these biotics on mental health. Eventually, they may be offered as treatment for mild depression or anxiety, rather than low-dose antidepressant or antianxiety medicines. (2)

Biotics may represent the next generation of medicines, potentially revolutionizing the way we prevent, manage, and treat diseases affecting the human body. So, what are they and how do they work?

Prebiotics encourage bacterial growth by serving as a food source for beneficial bacteria. They restore this good bacteria, enhance serotonin and dopamine production and reduce inflammation, which improves mood, reduces anxiety and depression, and enhances stress resilience.

Probiotics are live bacteria found in certain foods and supplements that add beneficial bacteria to your gut. They promote SCFA and neurotransmitter production, promote gut integrity, and modulate stress response. This reduces inflammation and HPA reactivity, improves cognitive function, and stabilizes mood. They are also able to remove harmful bacteria and exogenous substances from the body, thereby, reducing their impact and alleviating or treating diseases.

Synbiotics: Food ingredients or supplements that are a combination of prebiotics and probiotics working together in your digestive tract. Pre- and Probiotics may help to maintain long-term mental health despite a history of prior mental health issues.

Postbiotics: Healthy bioactive byproducts of probiotic bacteria when they digest prebiotic foods in the gut, creating the waste left behind. Unlike pre- and probiotics, postbiotics are not live microorganisms; however, they still provide health benefits and support bodily homeostasis and function. They include beneficial nutrients such as vitamins B and K, amino acids, and antimicrobial peptides that help inhibit the growth of harmful bacteria. Although postbiotics are more reliable, target-specific, and predictable, they are not widely used because they are relatively new compared to pre- and probiotics. However, research is being conducted to determine their benefits.

Psychobiotics (7): A new, emerging special class of probiotics with the added powerful ability to improve mood, reduce anxiety, and enhance cognitive function. Scientists are exploring these biotics as potential long-term treatments for mood disorders. Psychobiotic development hopes to provide relief in the treatment of mental health disorders, everyday stress, mild depression and anxiety, and neurodevelopmental (ASD, ADHD) as well as neurodegenerative disorders (e.g., Parkinson’s, Huntington’s). Multiple commercial psychobiotics have been developed to market, but more research is needed regarding regulation, side effects, and compatibility with specific patient populations.

Recently, the research community has been focusing on the connection between the GBA and health issues resulting from its dysfunction. Exploring the treatment of mental disorders through gut microbiome modulation is aiding in the development of new therapies that may be available soon. Currently, prebiotics are the most extensively researched. At the same time, clinical trials are being conducted on the use of probiotics to treat depression, anxiety, stress, cognitive impairment, and sleep disorders, as well as a range of GI disorders.

Meanwhile, an increasing number of patents related to biotics are emerging. There are multiple biotic supplements available on the market today, but regulation has been sparse, and not all of them are backed by adequate scientific research. If you are considering these options, consult your doctor and research their safety, potential side effects, and interactions with any other medications you may be taking before using them.

The reason probiotics work is that they fill a gap in the microbiome, thereby enhancing normal functioning. However, a diet that includes a diverse selection of plant-based options allows for a microbiome with a wide range of necessary bacteria, resulting in improved mental health. It is ideal to obtain the required variety of bacteria through your diet. However, the use of pre- and probiotics may still be necessary for a significant portion of people. Since the rise of processed foods in our diets, the population has fewer types of gut microbes than previous generations. This may decrease our ability to handle stress, so filling that gap with a proper diet, along with the use of biotics, could be beneficial. First, diversify your diet and eliminate chemicals; then consider adding psychobiotics.1,2

Other new and emerging GBA-focused treatments:

(11-13)

Fecal Microbial Transplant (FMT): A microbial transplant can restore the composition and function of the gut microbiome, reduce inflammation, and improve gut-brain communication. It may be helpful for people with hard-to-treat neurological disorders, like autism spectrum disorders (ASD).

Precision medicine: Treatment tailored to an individual’s gene variability, environment, and lifestyle. This is customized healthcare that utilizes microbial, genetic, and metabolic profiles to create personalized interventions aimed at altering the microbiome to improve health outcomes. The treatments include individualized nutrition and biotics, with genomic and metabolic analyses.

AI tools: Researchers are utilizing AI tools to assist in microbiome and metabolic analyses, targeting the GBA to predict which metabolites will bind to which receptors by predicting their shape. Machine learning is also being used to spot targets for novel pharmaceutical approaches to treat microbiome-related diseases.

SCFA-targeted therapy (14): Derived from the gut microbiota, they exhibit anti-cancer effects in several types of cancer. SCFA engineering is being done to allow targeted-delivery therapeutics for rare cancers.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS): A method used to read the sequence of DNA or RNA much faster and cheaper than old sequencing technologies. NGS has dramatically expanded our knowledge of the composition, diversity, and roles of the gut microbiome in human health and disease. It is being used to build a comprehensive atlas of specialized cell types in the GBA, expanding our knowledge of its physical makeup. This has allowed for preclinical trials involving microbial composition manipulation through dietary intervention, biotic supplementation, and FMT. NGS from GBA studies has allowed researchers to:

Analyze the composition and diversity of gut microbiota

Analyze gene expression patterns to better understand how certain microbes are related to mood disorders and neurodegenerative diseases

Identify how genetic variations affect gut microbiota and how microbial metabolites influence gene expression in the body

Identify microbial contributions to neurotransmitter pathways

Identify biomarkers for mental health and other neurological conditions

Develop microbiome-targeted therapeutics (targeted probiotics, FMT)

Support individualized nutrition and medicine strategies for brain health

The world of biomedical research, science, and medicine is on the cusp of a huge breakthrough. We are finally beginning to understand the holistic nature of the human body and the vital connection between brain and gut health. Individualized gut-targeted therapies as standard of care may be on the horizon. In addition, innovations such as engineered gut bacteria, microbiome transplants, precision biotics, and tailored diets may also become available, potentially offering better overall health to millions. But, there is still work to be done. A multidisciplinary approach would be ideal, encompassing the fields of psychology, psychiatry, nutrition, lifestyle medicine, and primary care; however, due to current standards, this is not an option for most people.

Also, as new treatments emerge, minority populations rarely see the benefit of new modalities and may be left out. Let’s explore how discrimination not only contributes to a poor GBA but also causes barriers to information and the kinds of treatment that could help.

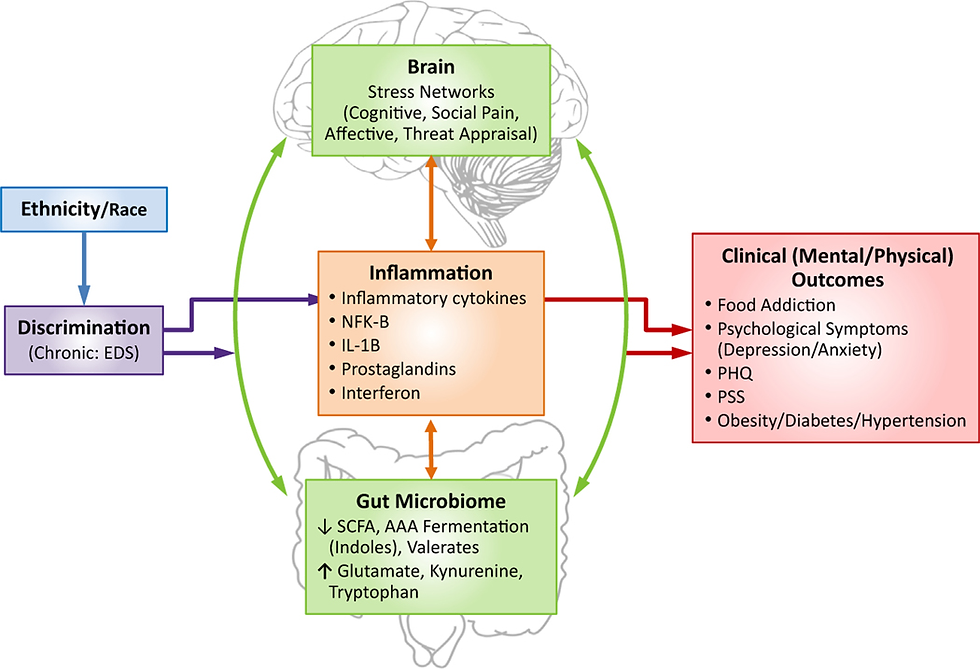

Discrimination and Its Impact on Gut Health (1,2,8-11)

Now that we understand the importance of maintaining the health of your GBA, we need to acknowledge that achieving this balance is especially challenging for minority populations, who often face food deserts, economic barriers, and limited access to nutrition and health education. Discrimination-whether based on race, gender, religion, disability, sexual orientation, or socioeconomic status– can create significant chronic stress. It can be experienced as when we form our perceptions of the world around us in childhood. This leads to chronic, lifelong exposure to stress, which has been linked to negative physiological effects, including disruptions in the gut microbiome, along with all the adverse effects we've discussed. Referred to as allostatic load, these populations experience chronic stress, which creates a cumulative burden on the body, leading to mental and physical disease.

The exact mechanisms by which discrimination leads to inflammation, obesity, and related disorders are still unclear. Current literature has mainly focused on genetics, diet, physical activity, and psychological factors. Recent research has revealed the sensitivity of the gut microbiome to stressors and how maintaining a healthy microbiota impacts inflammation and long-term health. However, more research is needed regarding the biological role of all forms of discrimination as the driving factor behind minority alterations in the GBA and its consequences.

Studies have shown links between discrimination and an altered GBA, leading to:

Inflammation

Cognitive, memory, and learning impairment

Poor impulse and inhibition control, especially in stressful situations

Poor coping mechanisms to deregulate from distress

Obesity

Cravings for hyperpalatable, high-calorie, low-nutrient foods (UPFs) and sweets

Poor impulse control

Anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, ASD, ADHD, schizophrenia, and other mental and emotional disorders

Altered pain responses: For example, visceral sensitivity , which is an increased sensitivity to pain in the internal organs, with a lower pain threshold, often leading to chronic pain

Altered regulatory functions in the brain that are critical for adapting to internal or external challenges, but also trigger emotion, decision making, and promote social behavior

Altered brain networks related to:

Emotion, causing heightened responses in: emotion regulation, alertness (hypervigilance), attention toward certain stimuli, and autonomic responses

Cognition

Self-perception

Pain-related processing

These alterations put individuals at higher risk for both mental and physical health problems. They also decrease the quality of life and the ability to function well in society, causing these population to be at a disadvantage from birth.

Key Factors in Minority Population That Contribute to GBA Dysfunction:

Sleep Disruption and Circadian Misalignment:

Shift work and unsafe or unstable housing conditions disrupt sleep patterns

Poor sleep worsens GBA function and brain health

Chronic Psychosocial Stress: Persistent exposure to discrimination triggers a prolonged stress response that activates the HPA, causing increased cortisol and inflammatory cytokines, which leads to:

Disrupted gut motility

Altered microbiota composition

Leaky gut

Dysbiosis: Reduced microbial diversity found in minority communities due to:

Increased early-life exposure to negative environmental stimuli

Chronic stress

Poor dietary habits, due to food insecurity, poor nutrition education, and access barriers

Diet and Nutrition Inequities:

Food deserts, limited access to healthy foods, and a low fiber diet (needed for GBA integrity and anti-inflammatory signaling)

High intake of UPFs and added sugars

Environmental Toxins and Pollutants: Higher exposure to air pollution, heavy metals, endocrine-disrupting chemicals (e.g., from poor housing habitats or proximity to industrial areas)

Healthcare Disparities:

Limited access to culturally competent care: leads to delayed diagnosis and treatment of disorders and limited access to preventative education.

Under-treatment of GBA-related conditions, like mood disorders

Barriers to treatment due to finances, transportation, and fear of modern or culturally inappropriate medicine

Epigenetic and Intergenerational Effects: Chronic stress induces epigenetic changes that may be transmitted to future generations, thereby increasing vulnerability to GBA-related disorders.

Mental Health Stigma:

Cultural stigma related to seeking help for mental disorders may cause unmanaged depression, anxiety, or other brain disorders, causing GBA alterations that exacerbate these conditions

Untreated psychological stress causes a vicious cycle

CHRONIC STRESS AND ALLOSTATIC LOAD

Individuals experiencing discrimination are exposed to increased chronic stress, which alters the GBA, including the vagus nerve, immune-inflammatory mechanisms, altered microbial metabolites, neurotransmitters, and the HPA axis. Recent neuroimaging studies found that dysbiosis was related to greater amygdala activation, creating more emotional reactivity, anxiety, and stress responses. It also caused decreased activity in the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for controlling emotions and cognitive functions such as decision-making and impulse control.

The allostatic system regulates our stress response, shaping the onset of physical and mental health disorders based on past and present environments. Negative environments, particularly poverty, often faced by minority populations, contribute to chronic stress, which is linked to inflammation, dysbiosis, and an increased risk of poor health. These factors adversely affect the interactions of our biological barriers, resulting in detrimental impacts on learning, memory, and impulse control. The allostatic system should be able to adapt to environmental demands, adjusting equilibrium during prolonged changes in allostatic mediators, such as cytokines from the immune system and steroids from the HPA axis. This dynamic nature is crucial for maintaining homeostasis throughout life, especially during periods of environmental change.

However, there is a threshold for stimulation within our bodies. Chronic or severe stress can lead to allostatic overload, overwhelming the system and preventing it from maintaining homeostasis, which can result in illness or even death. The cumulative effects of the burden created by chronic stress are referred to as allostatic load. While some individuals can seemingly cope with large amounts stress and return to baseline—a phenomenon known as resilience—others may struggle.

When psychiatric illnesses manifest, the stress response has become so heightened that it has damaged the blood-brain barrier (BBB), leading to neuroinflammation, cognitive deficits, and mental health disorders. A properly functioning GBA and its constant communication are essential for adapting to environmental influences and their effects on cognition, behavior, and mood. Maintaining a healthy barrier system is vital for fostering adaptive mechanisms to stress, facilitating learning, and promoting healthy social interactions.

Biological pathways demonstrate how chronic stress related to discrimination can lead to an altered GBA.

Brain: Chronic stress can actually rewire the brain to alter:

The executive network of the brain, which controls decision-making and impulse control, can lead to behavioral problems, cognitive dysfunction, poor eating habits, and inflammatory stress responses.

The responses in other brain regions responsible for reward processing and appetitive responses lead to unhealthy food cue responses, resulting in the deactivation of areas responsible for making good choices and increased activity in regions associated with increased appetite. This elicits increased cravings toward unhealthy foods with little nutritional value.

Stress networks can alter GI processes like motility, gut permeability, and microbial gene expression.

Cognitive, social, pain, affective, and threat appraisal cues are all affected

Leaky gut: Discrimination can alter the gut microbiome itself. Stress can lead to dysbiosis, which in turn increases gut permeability, triggering a systemic inflammatory response throughout the body. Stress-induced poor dietary habits contribute to dysbiosis, which can lead to dysregulated eating behaviors and an increase in harmful gut bacteria.

Glutamate: A neurotransmitter involved in GBA communication. Dysregulation of metabolism contributes to CNS inflammation associated with stress-related disorders like obesity, depression, and anxiety. Stress in early life has been recently linked to altered gut metabolites that may impact glutamate and stress mechanisms in the body. These metabolites were found to be related to altered brain function pathways involved in cognitive, emotional, and reward processing, as well as executive control.

HPA: An altered GBA leads to dysregulation of the HPA, resulting in elevated cortisol levels, which in turn lead to adverse effects throughout the body.

Gut metabolites: Chronic stress leads to a decrease in the production of protective metabolites (SCFAs, BDNFs) and an increase in the production of harmful, proinflammatory metabolites.

Vagus nerve: When neural signalling between the brain and gut is altered due to vagus nerve modulation, it causes multiple changes in behavior and mood.

Immune-inflammatory mechanisms: There is an increase in inflammatory cytokines in response to chronic stress.

All of these alterations are interconnected, occurring in a cyclical manner, creating a vicious cycle of stress, altered GBA, and disease.

One study found discrimination-related adverse biological changes such as: (9)

Increases in harmful bacteria that has been linked to inflammation, rheumatoid arthritis, and hepatic fibrosis

Decreases in anti-inflammatory and cardioprotective byproducts

Higher levels of metabolites involved in lipid metabolism, which can predispose people to high cholesterol

Lower levels of branched-chain fatty acids (similar to SCFAs), which have anti-inflammatory and anticancer properties, are important to gut motility and health.

Higher levels of inflammation-related compounds in the body, implicated in pain, chronic inflammatory disorders, and autoimmune conditions

OBESITY:

Discrimination is a psychosocial stressor and is considered to be an environmental risk for multiple diseases and disorders. It has been linked to unhealthy eating habits, which contribute to GBA alterations linked to stress, inflammation, and obesityf. People in marginalized communities tend to have increased brain activity in regions responsible for increased appetite and higher cravings to consume UPF-type foods that are hyperpalatable and contribute to unhealthy eating choices. This group also had higher levels of harmful gut bacteria, which disrupted crosstalk between the brain and the gastrointestinal system. Neuroimaging studies have shown that stress can alter food-cue reactivity to unhealthy foods, more prevalent in some minority communities.

A recent study, funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), analyzed brain activity and gut microbiota along with lifetime experiences of discrimination to investigate this topic. The individuals in the high-discrimination group exhibited higher brain activity, particularly in brain regions associated with reward processing, motivation, and impulse control, in response to all food images compared to the low-discrimination group, but especially to the unhealthy foods. The participants in the high-discrimination group also expressed a higher willingness to eat the unhealthy and sweet foods they were shown.(8)

Glutamate was found at significantly higher levels in the high-discrimination group. It plays a role in the brain’s response to food cues, and higher levels are associated with inflammation and obesity. These results indicate that a person’s GBA may change in response to ongoing discriminatory experiences, which can impact food choices, cravings, and brain function. It may show a link between people chronically exposed to discrimination and being at higher risk for obesity and related disorders. These populations could benefit from treatments related to discrimination-related stress-induced GBA alterations, but more research is needed.

ENVIRONMENT (10,11):

A person's environment is known to have a significant impact on their physical and mental health. Every living organism is at least partially shaped by its surroundings, which are perceived through social, physical, and emotional engagement. Environmental stimuli affect everything in our bodies, from our genomic makeup to our ability to develop and adapt. The blood-brain barrier (BBB) and the GBA not only communicate with each other but also maintain constant communication with the environment through an intricate network of interactions that shape our behavioral and cognitive functions. This refers to the physical, as well as emotional and social environments that we experience. It is referred to as barrier effects.

The biological barriers of the gut and brain serve as key interfaces that mediate communication between the body and its environment. Social interactions, pollution, stress, and physical surroundings influence the barriers in specific ways that produce physiological effects. The GBA doesn’t just mediate external stimuli; it also senses and responds to changes in the information being sent. The immune response, along with your GBA, is particularly sensitive to the surrounding environment, and both fluctuate in response to conditions such as temperature and air pollution. Physiological stress in response to harmful environmental stimuli activates the HPA, which communicates with the GBA, causing steroids to be released into the blood that have barrier-interacting effects, modifying permeability and responsiveness to stimuli. This allows inflammatory mediators to infiltrate the bloodstream and brain, resulting in physical, cognitive, and emotional responses.

Changes outside the body can lead to structural and functional changes inside. Currently, it is known that a person's environmental conditions influence neuroplasticity and functional connectivity in the brain, as well as the connections between the brain and the gut. Furthermore, the growth of cells, structures, and blood vessels in the brain is also impacted. Evidence indicates that external changes cause alterations in the immune system, microbiome, and the HPA axis. These responses happen independently of the brain but are still essential for cognitive and behavioral reactions to environmental changes.

Many minority populations live in areas with higher levels of pollution, crime, and poor housing, with limited access to healthcare and healthy foods. Barrier effects trigger biological responses, resulting in a range of adverse effects on the body that manifest in physical and behavioral consequences. These barrier-environmental responses are subject to change throughout the lifetime, with negative stimuli at critical life changes creating long-lasting or even permanent damage.

The structural complexity of one’s environment can provide learning opportunities, leading to the development of pathways in the brain that improve our mental functions. However, a lack of it can prevent us from accessing these opportunities, leading to fewer opportunities for growth. For example, higher socioeconomic status is associated with better housing, more leisure time, and greater travel options, leading to more new experiences compared to those who lack the same financial freedom. The brain is constantly shaped by new learning and experiences, but these are not always easily accessible.

Regular physical activity is one of the most important modifiable factors affecting our health and is known to benefit both the body and mind. It is often a controllable activity that causes changes to the GBA. Physical activity boosts our immune system, protecting us from disease, and enhances the brain region responsible for reward processes. Exercise is linked to microbiome changes that decrease inflammation and improve immune system regulation. Regular voluntary exercise also enhances memory, learning, mood, and lowers the risk of psychiatric disorders.

Environmental constraints can create barriers to regular exercise, reducing the opportunities for a person to remain active. For example, levels of physical activity within a community correlate positively with the availability of parks and public spaces, and negatively correlate with socioeconomic barriers to physical activity, such as the lack of safe outdoor spaces for exercise.

Environmental Impacts Throughout the Lifetime:

As early as the womb and throughout the lifespan, the environment has the potential to modify our GBA and barrier functioning. There are developmental stages, marked by periods of heightened sensitivity to environmental triggers, both positive and negative, that involve the BBB and GBA. These sensitive periods are crucial in determining whether the body develops properly to sustain normal physical and emotional functioning. When these periods are filled with environmental stressors, dysfunction is seen and may be permanent. For example, the maternal environment can modify the development of the BBB and GBA barriers in the fetus. A poor maternal environment can increase transgenerational susceptibility to harmful factors like toxins, viruses, or a predisposition to unhealthy diets, as well as contribute to future stress reactivity through the release of stress hormones and brain receptors that cause anxiety. Favorable environmental maternal conditions, on the other hand, can result in reduced anxiety as far out as during the child’s adolescence or adult life.

After birth and during childhood development, critical periods occur before full maturation. Environmental modifications during these periods play key roles in altering barrier functionality. Additionally, the brain's connectivity and vascular architecture are refined. During BBB development, stressors, whether newly introduced or present during this period, can have lasting effects on brain function and behavior, particularly during critical developmental stages. However, an enriched environment combined with a healthy diet can counteract the deleterious effects seen in poor environments. The mechanisms behind this and the extent of damage reversal need further study to develop preventative strategies for overcoming the negative short- and long-term effects of stressful early-life events and age-related impacts on stress response, barrier permeability, and brain function decline, since the integrity of these barriers is essential to learning, memory, and emotional regulation.

Cognition, memory, and learning are influenced by the microbiome. The GBA has been implicated in childhood and progressive neurodevelopmental disorders like ASD, ADHD, poor impulse control, and concentration issues. Gut microbes impact the production of neuronal growth in the brain, which is essential for learning and long-term memory.

The interactions between the body and its environment have important implications regarding physical and mental health disorders. Increasingly, evidence shows that disruptions in the environment-barrier communication system predispose individuals to a wide array of psychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder (MDD), bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. Chronic social, physical, and psychological stress will create anxiety and/or depression via damage to the GBA and BBB. Environmental stressors like social isolation, low socioeconomic status, and sedentary lifestyle have been linked to systemic inflammation and risk for a multitude of psychiatric and physical maladies.

Meanwhile, positive environments that include good psychosocial components like physical exercise, higher socioeconomic status, and social support are protective against disease and tend to decrease the risk of mental health disorders.

Increasingly, evidence shows that persistent disruptions in the environment-barrier communication system as early as fetal development, predispose individuals to a wide array of psychiatric disorders, with genetics contributing around 60% increased risk for schizophrenia and up to 30% for MDD. This suggests disrupted GBA-BBB pathways among people who suffer from these crippling disorders, and research has found that they are well known to have a loss of barrier integrity. Environmental stressors like social isolation, low socioeconomic status, and sedentary lifestyle have been linked to systemic inflammation and risk for a multitude of psychiatric and physical maladies. Meanwhile, positive environments that include good psychosocial components like physical exercise, higher socioeconomic status, and social support are protective against disease and tend to decrease the risk of mental health disorders.

Despite the fact that it is well known that barrier integrity plays a significant role in these mood disorders, the communication between these systems is still unclear. Addressing the role of the GBa and systemic discrimination-related disoreders is crucial for improving both mental and physical health outcomes in minority communities.

POLLUTION: (11)

Air pollution has become a global healthcare issue. Airborne contaminants are known to cause disease and affect overall health negatively, causing chronic conditions like Parkinson’s, diabetes, memory issues, as well as heart, respiratory, and brain diseases. The oral and gut microbiota are key portals through which external compounds enter the body. The oral-intestinal-brain axis network is closely intertwined, so an insult to one area can be rapidly spread throughout the body. Air pollutants cause negative health impacts by causing inflammation in the brain, GI system, and lungs, which goes on to create body-wide consequences. In addition, chronic exposure to external pollutants alters certain epigenetic processes.

As we’ve seen, the microbiome is responsible for regulating immune responses, metabolizing nutrients, and preventing the entry and colonization of pathogens. Air pollutants, entering through the mouth, travel to the lungs and then affect the gut. Once toxins enter through the oral mucosa, they are primarily absorbed into the bloodstream and then distributed to the lungs. Inhaling these toxic particles causes respiratory inflammation, which disrupts the microbiome and leads to further inflammation. Because the body is interconnected, interactions between the lungs and gut allow lung damage to be easily transmitted to the GBA, worsening lung inflammation and creating a vicious cycle.

In addition, pollutants can be swallowed and enter the GI tract directly through contaminated food and water, directly harming the microbiome. Disruption of intestinal flora leads to multiple disease states and has a direct impact on brain function. Pollution can also have a direct effect on the CNS from an early age. Systemic inflammation caused by pollutants makes the BBB more permeable to toxins, creating neuroinflammation and causing damage to regions responsible for cognition, movement, and other nervous system functions.

Pollutants alter various epigenetic processes by modifying DNA methylation patterns and changing gene expression. Persistent exposure to pollutants is linked to various epigenetic mechanisms. Chronic exposure leads to all GBA-related diseases, including lung and neurological disorders. However, further research is still needed related to pollution-related neurological disorders.

CLINICAL APPLICATIONS:

Minority populations and individuals who face regular discrimination are at a much higher risk for multiple negative outcomes, many of which involve the BGA. While most people experience unfair treatment at some point, marginalized communities may face this daily. How they perceive and process discrimination is altered by chronic changes in the brain and gut. The saying “racism makes me sick to my stomach” may have a real physical basis.

Higher levels of discrimination are linked to more microbiome disorders, inflammation, and mental health issues. Socioeconomic status, lifestyle choices, and physical appearance have a significant impact on individuals' physical and emotional well-being in society. People facing discrimination tend to have higher levels of anxiety, depression, and visceral pain, along with reduced activity in brain pathways involved in problem-solving, coping, and decision-making, which are essential for functioning well daily and in stressful situations.

Starting as early as childhood, discrimination exposes individuals to poor environments, a lack of resources, and unhealthy eating habits. This results in deficits in memory, cognition, learning, problem-solving, and impulse control. These issues, in turn, contribute to continued poverty, lower educational attainment, and fewer financial opportunities. Moreover, physical and emotional disorders only worsen these problems, making it harder for minorities to succeed.

Strategies for Supporting Gut and Mental Health in Minority Communities

To improve mental health outcomes through gut health, a holistic approach is necessary. To address the underlying causes and promote overall well-being, a combined effort involving governmental, medical, and community efforts is needed. This could open new possibilities for tackling the clear disparities between populations and could advance the prevention and treatment of health issues related to minorities.

Key strategies include:

Culturally Inclusive Nutrition Education – Providing accessible information on gut-friendly diets tailored to cultural preferences.

Community-Based Mental Health Programs – Expanding mental health services that integrate dietary and lifestyle interventions.

Policy Changes to Address Food Deserts – Advocating for better access to nutritious foods in underserved areas.

Reducing Discrimination-Related Stress – Implementing stress management programs to mitigate the physiological effects of discrimination.

Future Suggestions:

Research: Current studies have been limited by small sample sizes, short study durations, and diverse research designs, necessitating further investigation to understand the GBA and its impact on mood and behavior. Further research should include:

Larger, more diverse populations are needed to establish causal links and assess the long-term efficacy of microbiome-targeted therapies, thereby facilitating the translation of findings into clinical practice.

Concentration on the clarification of the gut-brain-immune axis mechanics and application of the results to clinical practice.

A drug discovery program focusing on stress-related changes in GBA and BBB, aiming to gain a better understanding of pathways related to chronic stressors and allostatic load. It could target the pathological features of mood disorders associated with chronic discrimination-related stressors and environmental impacts.

The potential for microbiome modulation via biotics and fecal transplant.

Standardization of biotic formulations and dosing to facilitate their medical use.

Identify environmental influences in early life that impact development and increase the risk of mood disorders.

Proactive studies to investigate preventative pathways, rather than just treating symptoms after the disease is present. They could focus on the positive effects of altering harmful environmental stimuli, including social interactions, environmental complexity, and access to nutritious food, as well as the impact of introducing new, stimulating educational experiences and physical activity.

Federal regulation of biotic claims: FDA regulation through food industry claims or by making biotics a medicine. Multiple companies have touted the use of biotics in their supplements, but these products often include added sugars, and their claims are not backed by sound science. Previously, regulation of these claims was not being well monitored, but that may be changing

Food availability: It is well known that people living in areas of lower socioeconomic status often face food deserts and a higher number of places offering poor food choices. An effort should be made to increase access to places with nutritious food.

Individualized Treatments: Since every person’s microbiome is unique, standard treatment algorithms may be ineffective. Using clinical manifestations, past medical history, and recent research guidelines in a culturally sensitive and inclusive manner to create holistic, individualized treatment plans for patients would be beneficial. However, individualized treatment may not be accessible to all, as it is not typically covered by insurance and will be expensive.

Educational Outreach: Development of low-cost, highly effective strategies to promote a healthy lifestyle and improved mental health.

Mental Health Providers: Integration of personalized microbiome-based science into precision psychiatry to revolutionize mental health care.

Nutrition:Improve patient outcomes by implementing cost-effective educational outreach focused on prevention and the management of psychiatric and emotional challenges. This initiative will advocate for health-promoting dietary habits, address nutritional deficiencies—especially those common in marginalized communities—and encourage healthy lifestyle choices that contribute to better mental health:

Include appealing and engaging materials in the community and in doctors' offices with pertinent information.

Awareness campaigns that are created for minority populations.

Informational seminars for health care providers explaining how to include this information in every patient's plan of care.

Political pressure to incorporate insurance-covered interdisciplinary care that includes nutrition, lifestyle medicine, neuroscience, and psychiatry.

CONCLUSION:

Although the GBA has been acknowledged for centuries, we are only now starting to grasp its complexities. There is a clear need for new therapies that are safe, effective, and can be combined with existing treatments to enhance patient outcomes. As our understanding of the human body has advanced, it has become increasingly clear that diseases rarely occur as isolated events caused by just one or a few biological factors. Instead, the human mind and body are an interconnected system of cells and microorganisms, forming a whole, and when one part is disrupted, the entire organism can be affected. To address this, a multifaceted and holistic approach is essential. Our understanding of how the microbiome influences the body continues to grow, driving significant investment in research within both academia and industry to find ways to modulate the GBA for treating a wide range of diseases. There is a strong push to better understand the molecular and biological mechanisms that trigger the GBA in order to improve the discovery of new therapeutics. However, more research is needed to understand how discrimination and chronic stress activate the GBA and how we can combat this societal issue.

The homeostasis of the GBA is vital for the proper development and maintenance of digestive and mental functions. Dysbiosis of the microbiome is now recognized as a major contributor to a variety of diseases, including mental, metabolic, and digestive disorders. Thanks to increased research efforts to classify microbial populations and their functions, there has been robust progress toward new and innovative approaches, such as biotics, artificial intelligence tools, and next-generation gene sequencing technologies. The communication between the gut and brain is now beginning to be understood. Moving forward, we need to investigate why and how this communication occurs and determine the most effective ways to modulate the microbiota for therapeutic purposes. However, microbiota vary greatly among individuals, with each individual having a unique microbiome, which requires personalized healthcare strategies. This variation can complicate studies seeking specific biomarkers. The knowledge we are acquiring about the microbiome and its communication pathways can be used to enable early prediction of diseases such as autism and Parkinson’s. With early diagnosis, we may be able to slow the progression of neurodegenerative diseases in the future and treat these conditions through microbiome modulation. Additionally, we can utilize this knowledge to prevent and mitigate the effects of environmental stressors on mental health.

Yet, more research is necessary to understand how discrimination and chronic stress activate the GBA and how we can address this serious societal challenge. The future may present unique opportunities for new treatments and management strategies for those already affected, along with universal preventive services for everyone, regardless of appearance or socioeconomic status. As human beings, we should give this issue the attention it deserves because every person is entitled to equal opportunities for a healthy life and the benefits that come with it.

References:

Sasso JM, Ammar RM, Tenchov R, Lemmel S, Kelber O, Grieswelle M, and Qiongqiong Zhou QA.Gut Microbiome–Brain Alliance: A Landscape View into Mental and Gastrointestinal Health and Disorders. ACS Chem Neurosc. 2023;14(10): 1717-1763.DOI: 10.1021/acschemneuro.3c00127

Crompton S (2019) Psychobiotics: your microbiome has the potential to improve your mental health, not just your gut health. Science focus. https://www.sciencefocus.com/the-human-body/psychobiotics-your-microbiom. Accessed: June 17, 2025.

Xiong RG, Li J, Cheng J, Zhou DD, Wu SX, Huang SY, Saimaiti A, Yang ZJ, Gan RY, Li HB. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Anxiety, Depression, and Other Mental Disorders as Well as the Protective Effects of Dietary Components. Nutrients. 2023 Jul 23;15(14):3258. doi: 10.3390/nu15143258. PMID: 37513676; PMCID: PMC10384867.

Merlo G, Bachtel G, Sugden SG. Gut microbiota, nutrition, and mental health. Front Nutr. 2024 Feb 9;11:1337889. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1337889. PMID: 38406183; PMCID: PMC10884323.

Tuhin,M. How Your Gut Health Affects Your Brain: The Mind-altering Power of Your Microbiome. Science News Today.2025 May 17. thttps://www.sciencenewstoday.org/how-your-gut-health-affects-your-brain-the-mind-altering-power-of-your-microbiome#google_vignette

Ji J, Jin W, Liu SJ, Jiao Z, Li X. Probiotics, prebiotics, and postbiotics in health and disease. MedComm (2020). 2023 Nov 4;4(6):e420. doi: 10.1002/mco2.420. PMID: 37929014; PMCID: PMC10625129.

Sharma R, Gupta D, Mehrotra R, Mago P. Psychobiotics: The Next-Generation Probiotics for the Brain. Curr Microbiol. 2021 Feb;78(2):449-463. doi: 10.1007/s00284-020-02289-5. Epub 2021 Jan 4. PMID: 33394083.

Zhang, X., Wang, H., Kilpatrick, L.A. et al. Discrimination exposure impacts unhealthy processing of food cues: crosstalk between the brain and gut. Nat. Mental Health 1, 841–852 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-023-00134-9.

Dong TS, Gee GC, Beltran-Sanchez H, Wang M, Osadchiy V, Kilpatrick LA, Chen Z, Subramanyam V, Zhang Y, Guo Y, Labus JS, Naliboff B, Cole S, Zhang X, Mayer EA, Gupta A. How Discrimination Gets Under the Skin: Biological Determinants of Discrimination Associated With Dysregulation of the Brain-Gut Microbiome System and Psychological Symptoms. Biol Psychiatry. 2023 Aug 1;94(3):203-214. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2022.10.011. Epub 2022 Oct 28. PMID: 36754687; PMCID: PMC10684253.

Paton SEJ, Solano JL, Coulombe-Rozon F, Lebel M, Menard C. Barrier-environment interactions along the gut-brain axis and their influence on cognition and behaviour throughout the lifespan. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2023 May 30;48(3):E190-E208. doi: 10.1503/jpn.220218. PMID: 37253482; PMCID: PMC10234620.

Chen S, Yu W, Shen Y, Lu L, Meng X, Liu J. Unraveling the mechanisms underlying air pollution-induced dysfunction of the oral-gut-brain axis: implications for human health and well-being. Asian Biomed (Res Rev News). 2025 Feb 28;19(1):21-35. doi: 10.2478/abm-2025-0002. PMID: 40231163; PMCID: PMC11994223.

Mehta I, Juneja K, Nimmakayala T, Bansal L, Pulekar S, Duggineni D, Ghori HK, Modi N, Younas S. Gut Microbiota and Mental Health: A Comprehensive Review of Gut-Brain Interactions in Mood Disorders. Cureus. 2025 Mar 30;17(3):e81447. doi: 10.7759/cureus.81447. PMID: 40303511; PMCID: PMC12038870.

Rathore K, Shukla N, Naik S, Sambhav K, Dange K, Bhuyan D, Imranul Haq QM. The Bidirectional Relationship Between the Gut Microbiome and Mental Health: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus. 2025 Mar 19;17(3):e80810. doi: 10.7759/cureus.80810. PMID: 40255763; PMCID: PMC12007925.

Son MY, Cho HS. Anticancer Effects of Gut Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Cancers. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2023 Jul 28;33(7):849-856. doi: 10.4014/jmb.2301.01031. Epub 2023 Mar 30. PMID: 37100764; PMCID: PMC10394342.

Franck, M., Tanner, K.T., Tennyson, R.L. et al. Nonuniversality of inflammaging across human populations. Nat Aging (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-025-00888-0

Author: Rachelle DiMedia

Assessed and Endorsed by the MedReport Medical Review Board